In philosophy, argumentation is elevated to being an art form. Arguing for something that might be generally considered absurd can be considered a useful exercise from a philosophical point of view, with a long tradition that dates back at least as far as Socrates. This writing is an example of an unconventional argument.

It has been widely commented that, in general, the media does not make us happier as individuals. When we look at social media on our phones, we are immediately inundated with an ugliness that in all likelihood does not exist in our present environment: police brutality, violence against animals, terror attacks, other violent attacks, protests, racism, fights, and so on. I don’t deny that these things happen. I don’t deny that for some unfortunate people, a “volatile” atmosphere is a fact of life, and it’s also true that no life, however seemingly secure, is free of risk. Here I would like to argue something that may at first sound absurd and counter intuitive: you should isolate yourself as much as possible from any and all knowledge of what is going on outside of your immediate sphere of experience and, when new information does enter that sphere, you should try your best to ignore it and not do anything whatsoever about it.

Lets say that you are vegan and, in looking for butter alternatives,  you landed upon Earth Balance at Whole Foods. You felt for a while that you were doing the right thing, but then you find out through social media that Earth Balance is made of palm oil, and that palm oil is responsible for the destruction of the native habitat for the endangered orangutan.

you landed upon Earth Balance at Whole Foods. You felt for a while that you were doing the right thing, but then you find out through social media that Earth Balance is made of palm oil, and that palm oil is responsible for the destruction of the native habitat for the endangered orangutan.

My argument here is that, even so, you should still continue to purchase Earth Balance, and only when the crisis is knocking on your front door should you do anything whatsoever to change your behaviors.

This argument of course is difficult to make and flies in the face of ethical theory. My behavior of continuing to purchase Earth Balance cannot be universalized for all, as would be suggested by a Kantian approach, without my also consenting to the destruction of the endangered species of orangutan. It’s equally difficult to justify from a utilitarian perspective. Allowing oneself to contribute to species extinction does not seem to promote happiness for humans or animals. It’s clear that traditional ethical theory does not bode well for my behavior, much less an environmental ethic.

Yet, there is no real contradiction in it if I am the sort of person who will willingly assent to the destruction of the orangutan. The point was clearly stated by Hume in his devastating critique of moral theory, which concludes concisely: “Since reason alone can never produce any action or give rise to volition . . . . It is in no way contrary to reason to prefer the destruction of the whole world to the scratching of my finger.”

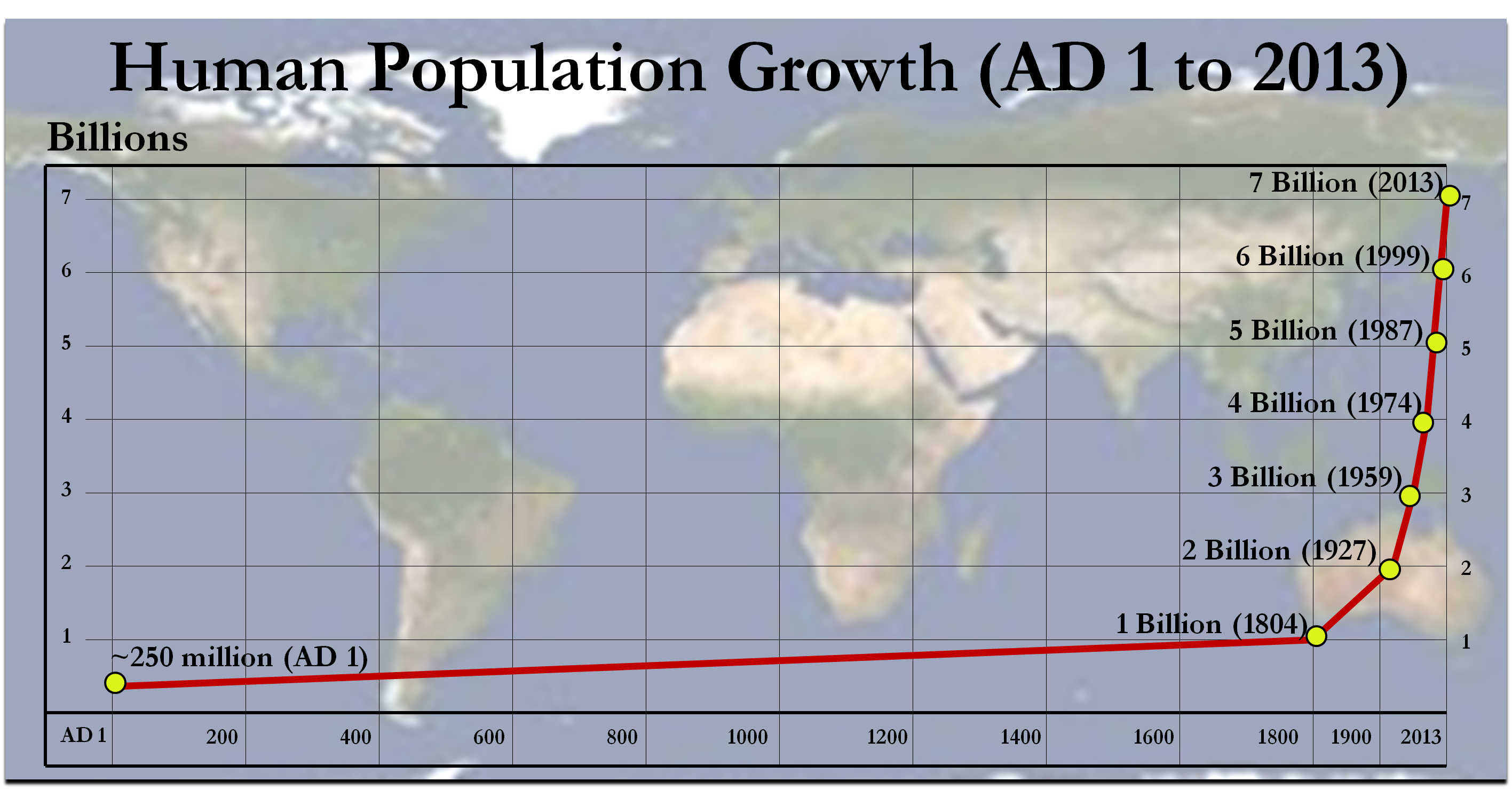

If there were only a dozen people on this planet, that dozen people would pose no environmental threat to this planet whatsoever, however they behaved. They could kill orangutans, lions, fish, really anything that they were capable of killing. They could pour oil into the water, burn tires, spray aerosol cans, and they would simply be incapable of making a dent in the vast well-stocked Eden which they inhabited. Their lives would likely be impoverished and barbaric, equally likely to perish as to survive as a species. Even if they did survive and reproduce, it would be a long while before their descendants were able to bring about the sort of global catastrophes we hear about on the news everyday.

One can view overpopulation as the fundamental problem that is leading to all of the other problems humanity has to face. Why are there factory farms in which innocent animals suffer and die? Why is the wilderness being destroyed for farm land.

If you view it in this light, there is very little you or I can do about it in our lifetimes, whether or not you do have kids. If you already have kids, it’s not like you’re going to kill them off. If you don’t have kids, then I suppose you can pat yourself on the back. I suppose you could decide to “not have” that other kid you were thinking about having. But, all this is in a way beside the point.

This is because even if you live your life as a saint, foregoing Earth Balance, following the Categorical Imperative, and going childless or not having that other kid, some guy down the street who abides by different ideals is going to take three wives, have twelve children, and negate or ruin the Eden that you spent your meager, solitary life trying to build. Not only that, but once you die with your ideals, his children, who are more likely to inherit his ideals, are going to continue to overpopulate the world, and the world will once again find itself in the same situation.

Incidentally, not overpopulating the world is one thing that Americans are good at, with a total fertility rate of 1.84, well below the replacement rate of 2.1. Our increase in population is the result of immigration. Of course, we offset this by our consumption. Our five percent of the world population is said to consume 20 percent of its resources.

It may be argued that this stance is a consequentalist one. If one takes the opposed Kantian/deontological approach, then one can theoretically say that certain acts are wrong/immoral in themselves. Thus, from the Kantian perspective, it’s always wrong to tell a lie, and it may always be wrong to purchase Earth Balance.

I don’t buy it, and I do not believe that it is even possible to construct an ethical theory that does not give a thought to consequences. Kant suggests to us that we universalize the maxim upon which we are acting in order to assess its moral value, and ask ourselves if we could assent to the results. Therefore, according to Kant, my act of telling a lie is wrong because I would not agree that it is ok for everyone else to do it.

One does have to think about consequences in order to apply the Kantian ethic. We always have to ask ourselves: what would happen if everyone acted this way? And this is a good thing. We don’t want an ethic in which we have all behaved in a saintly way, but in which we leave a hell for our children. But we also need to keep in mind that Kantian theory fails to overcome Hume’s critique. Even if everything were to go to hell if everyone lied all the time, it is in no way irrational to assent to it.

One does have to think about consequences in order to apply the Kantian ethic. We always have to ask ourselves: what would happen if everyone acted this way? And this is a good thing. We don’t want an ethic in which we have all behaved in a saintly way, but in which we leave a hell for our children. But we also need to keep in mind that Kantian theory fails to overcome Hume’s critique. Even if everything were to go to hell if everyone lied all the time, it is in no way irrational to assent to it.

This brings another point unconventional point to light. Lets say, in sympathy with an environmentalist ethic, that I do not agree to the destruction of the orangutan or the planet’s environmental degradation (plastics in the water, clear cutting of forest, species extinction, global warming, etc.) It may be the case that the large part of the work that I am capable of doing is determined by whether or not I decide to have children and how many I decide to have.

If I believe that the world is overpopulated already, then my decision to have more than one child is forbidden by the Kantian ethic itself. If I have two children, then I have neither contributed nor helped the problem. If I have more than two, I have made it worse.

If, as I have suggested, we always have to think about consequences when determining our behaviors, it is important for us to think about whether or not little efforts like forgoing Earth Balance, or larger efforts like going vegan will or will not make a difference in the long run given the steady increase of the human population, because it is that increase that is driving the demand that is causing the destruction. If we believe that our efforts will result in no net benefit, then it’s just as well we not trouble ourselves with them. In the words of Shakespeare: “Things without all resolve should be without worry, what’s done is done.”