In a recent New York Times column, Princeton economics professor Uwe E. Reinhardt bucks generally accepted market theory to argue against the all-volunteer army in the U.S.

The argument he addresses goes like this: Spreading military service across all societal strata (a draft) would place some of our most valuable economic assets (our brain surgeons, our bankers, our politicians) in harm’s way while denying those who could most benefit from a military paycheck (our poor, our patriots) from receiving this pathway to economic mobility.

As a lot of economic theory values efficiency above all else, many economists like this argument, as do those of us with comfortable lives that would be disrupted by a military tour in a far-away place littered with roadside bombs.

Reinhardt points out that because most people in Congress are millionaires (see the Center for Responsive Politics data on this), our decisions about going to war are fraught with moral hazard. The members of Congress who vote to wage war and the executives of companies that make billions selling goods and services to war efforts are not the same people losing limbs on the roadside. Reinhardt’s point is one about human nature and policymakers: If it were their personal limbs or those of their children on the line, would our decisions about going to war be different? If we created a ‘profit draft’ on corporations in which companies take losses when supplying goods and services to U.S. wars, would they still lobby for the war machine?

Harvard Professor Michael J. Sandel and others have drawn attention to a similar rich/poor divide in the U.S. blood banking system, which transfers blood from the poor, who are so destitute they sell it, to the rich, who have health insurance and the ability to buy and use blood as needed.

The same question applies to war and blood banks: Should a person of wealth be called upon to give away her blood when there is a poor person willing to sell it cheaply instead?

The economist’s answer is no, and for good reasons. Market allocation is brutally efficient. And what happens when the lawyer takes the place of the destitute in the blood line? The destitute person becomes worse off, not better, and the lawyer is taken away from lawyering, a more productive use of her time for the economy. So these questions about allocating blood become questions about the type of society in which we live, an area pure economics is ill-equipped to address.

Because, ideally, nobody would be so out of options that they feel compelled to sell their blood or risk having their limbs blown off.

Thinkers like Reinhardt and Sandel are not just arguing about economic theory, they are bringing up issues about how good we are as a society based on the rules we make. Their questions are existential for us as Americans. Do we sell our blood because human nature requires it, or is it just a matter of education? If we all understood how an all-volunteer military or a blood banking system transformed the suffering of the lower classes into profits for the upper, would we change our rules? Can suffering be legislated away?

I don’t know, and it is clear that when it comes to my everyday life, I follow market principles. Case in point: I posted a job on Elance looking for someone to perform what looked like 25 hours of data entry. This is how I met Candie (I’ve changed all the names) from Oklahoma, who said she and two of her associates were “ready to serve” and Micha, a former SUNY student with a sexy profile pic who said she was really hoping we could talk soon, and Raven in Tennessee, who assured me that her “clients are always satisfied.”

The job was to enter about 5,000 data points into a spreadsheet while confirming that 1,700 or so urls were real and alive. How much would I pay? I checked the box that said “Less than $500.” Within a couple of hours, about 80 people submitted proposals for the work. I could have it in one day. I could have it for $20. People with 20 years of experience were sending me their picture and asking me to call them. The Internet had turned the world into one giant Burger King where I could have it my way.

These higher-level concerns about markets, inequality and human suffering were not part of my thinking as I looked for someone to do this work, which, without Elance, would take me week to finish in-between my other chores, the final product I would create riddled with fat-finger typos and screwed up in places where I got distracted. I was focused on this pain being removed from my personal, privileged ass. This is the market at work and the only question for the market is: Who would do this, and for how much cheese?

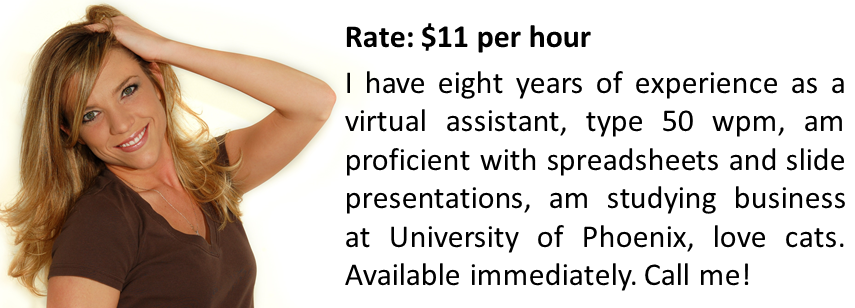

One applicant wanted the full five-hundo, about $20 an hour, $41,600 a year. This is a living wage on a world scale, and less than I would personally charge to do this data entry. Micha wanted $11 per hour, Candie wanted $12, even with two people helping her.

I support increasing the minimum wage in the U.S., like the idea of a ‘profit draft,’ would like to see the buying and selling of blood end in the U.S. But when it came to my personal allocation of resources, I bypassed all of what looked like living-wage offers and hired TJ, who offered to do all of this work for $27.40, a little more than $1 per hour. TJ lives in the developing world, where it is worth it for him to do three days of data entry for about $30, about 1/10th the going rate in the developed world.

In aggregate, all of the small businesses like mine, or large corporations buying labor from all the TJs for a buck an hour participate in our own kind of moral hazard. I benefit from TJ’s low living standards, while Candie and Micha and Raven are forced to ask for less and less. The market is self-perpetuating in just this way. The divide between those buying the labor and those supplying it bid one another down, and the companies that refuse to pay the lowest rates cannot compete effectively. Mine is not a business that can pay $20 an hour for data entry, and if I did, I would go out of business and nobody, not even TJ would be making anything.

Economics, the study of the allocation of scarce resources, only explains the cold, efficient levers of incentive. It will make note of the minimum standards of nutrition and shelter workers require to survive and contribute to the economy, but has few tools to account for humanist concerns. Economics does not cringe when a single mother in the U.S. competes for odd-jobs with someone in the developing world willing to work for $1 an hour. The question of how to create a better situation for both of these people when their interests seem in opposition is bigger than economics, which is why thinking about it will only become more important as the divide between rich and poor, decision-maker and worker expands in the U.S. and the rest of the world.