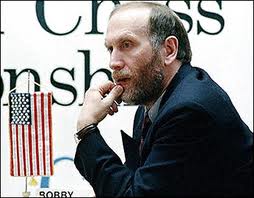

In 1992, a 49-year-old Bobby Fischer emerged from a 20-year seclusion to play for a $5 million prize against Borris Spassky in Sveti Stefan, Yugoslavia. One of the spectators that showed up to watch the match was an 81-year-old Russian grandmaster whom Fischer had never met named Andrei Lilienthal, who was living across the border in Budapest. Fischer’s words of greeting:

“Hastings, 1934/35: the queen sacrifice against Capablanca. Brilliant!”

Here, Fischer was referring to a match that took place nine years before he was born, between two chess masters he had never met. It was a moment of pride for the old grandmaster, one that he would never forget (Brady 251).

Frank Brady has done a great service in the publication of the newest biography of Fischer, Endgame: Bobby Fischer’s Remarkable Rise and Fall. Brady’s biography will certainly do a lot in the way of clearing up many popular myths about the man and his life. Throughout the book, which fills 411 pages, we are given glimpses into the real story, which is nothing if not complex. How do we reconcile the darker sides of Fischer, his anti-Semitic and anti-American remarks, his ridiculous demands, with his charming moments, like the one mentioned above? Using Brady’s biography and other sources, I here attempt to clear up some myths and to offer some original ideas about the man.

In Brady’s book, he makes reference to a particular article written for Harper’s in 1962, when Fischer was 18. Fischer’s resume at this time was already impressive. He had just won his fourth consecutive U.S. Championship, the first when he was only fourteen. Perhaps more impressively, at the age of 15 Fischer had succeeded in the first round of the Candidates tournament, to be one of six vying for a chance to play for the World Championship against Botvinnik. Eventually, Fischer lost in the final round to the 22-year-old Mikhail Tal. (More on this later.)

The Harper’s article was written by Ralph Ginzburg, a journalist who had worked for Look and Esquire. Ginzburg would later be indicted and serve time for publishing obscenity in a pseudo-pornographic magazine that he founded called Eros. It might be fair to say that Ginzburg had a penchant for seediness and sensationalism. In many ways, the publication of the Harper’s article would be a turning point for Fischer in the way Fischer viewed journalists in general. On account of its popularity, the article was also a turning point in how the media and public at large viewed Fischer.

We will never know how much of what Ginzburg related was factual because, when questioned, Ginzburg claimed to have destroyed all of the research materials. Still Brady, who knew Fischer personally and who can rightfully claim to know more about Fischer than anyone, refers to the article as a “penned mugging.”

Upon first reading the article, nothing really stood out to me as particularly heinous or spurious. In the lengthy quotes that Ginzburg attributes to Fischer, Ginzburg seems to have Fischer’s dialect down pat, and many of the things that the 18-year-old Fischer says seem to foreshadow remarks that he would make later in life. On the other hand, it would not have been difficult for Ginzburg to emulate Fischer’s way of speaking, since they both haled from the Bronx. Still, the young Fischer was livid when he came across the article reprinted in the British magazine Chess. From Brady:

Previous to this, Bobby had been wary of journalists. The Ginzburg article, though, sent him into a permanent fury and created a distrust of reporters that lasted the rest of his life. When anyone asked about the article, he would scream: ‘I don’t want to talk about it! Don’t ever mention Ginzburg’s name to me!’ (Brady 138)

How are we to tease out truth from sensationalism in this case?

Background

Fischer’s life is as much the story of the angelic and Herculean benefactors that protected him as it is that of the greatest chess player of all time. First and foremost of these was Regina Fischer, his mother. She was perhaps the lone angel of the group, because, with her charm, wit, brilliance, and endless industry, she brought the others into his life.

It is not an exaggeration to say that Bobby was born into poverty. In the midst of World War II, Regina had first fled Stalinist anti-Semitism to France. Then, as the Germans were preparing to invade France, she fled again to the United States with her young daughter Joan. Her husband, Hans Gerhardt Fischer, a biophysicist, was unable to come along on account of his German citizenship. Regina had had to leave behind the six years of study she had put in towards becoming a medical doctor in Moscow without obtaining a degree. Upon arriving in America a single mother stripped of her credentials, Regina traveled to numerous states, working different jobs. At some point during this time, Bobby was conceived. When Bobby was born, Regina was living in a shelter for single mothers in Chicago, and Joan was staying with her grandfather. When Regina had Joan sent to the shelter to be with her, she was not admitted, and the family was kicked out of the shelter. Regina put up a fight, which led to charges against her, which where later dropped.

Bobby’s first years were nomadic ones, with Regina moving as far West as California, working numerous jobs as a “welder, school teacher, riveter, farm worker, and stenographer,” before finally settling in the Bronx, New York. (Brady)

New York seems to have brought a measure of stability, but also seemingly endless hours of work for Regina. She worked mainly as a stenographer, returned to school to become a nurse, and also relied on some government assistance to get by. She would eventually not only get her nursing degree, but go on to obtain her M.D.

A close examination of the events shows this much to be clear about Regina: She was a dedicated mother in an extremely compromised position who did everything in her power for her children.

A close examination of the events shows this much to be clear about Regina: She was a dedicated mother in an extremely compromised position who did everything in her power for her children.

When Regina was not around, Bobby was in the care of Joan. Still, Regina tried to keep them mentally occupied by providing board games and puzzles for their diversion, always emphasizing the importance of education. One of these games was a plastic chess board, brought from the candy store for a dollar. The young Joan and Bobby learned to play on their own, with Joan reading the instructions. Bobby had shown an immediate strength and fascination in the game, which may have contributed to Joan’s blase attitude about it. Thus, Bobby was left with no partners to play against in this two person sport, and spent time playing games against himself.

As Bobby became older, it became clear to Regina that there was something amiss. While Joan progressed normally and was an exceptional student, Bobby seemed to have trouble relating to others in any context, and his chess obsession grew.

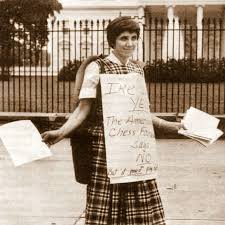

Regina protesting solo outside the White House, trying to get a ticket for her son to the Candidates tournament.

In Brady’s book, we can see clearly that Regina’s behavior is that of a worried mother. She brought him to numerous counselors and doctors, something that could not have been easy given her meager income at the time. She was not below asking for pro bono help. Most of the doctors dismissed her claims. The typical response she received was that she shouldn’t worry, and that there were worse things her son could be involved in than chess.

A Potential Diagnosis

When one looks closely at the facts, it is clear that Regina’s intuition was correct, but the psychiatry of the day did not have an accurate enough lens to see it. Brady describes some of Bobby’s symptoms:

At thirteen, his behavior in chess tournaments and in clubs was quite benign, but like many teenagers he was sometimes too loud when talking, clumsy while walking past games in progress, unkempt in grooming, and a perennial ‘bobber’ at the board. (Brady 70-71)

To this list of symptoms, one might also add an apparent lack of empathy and awareness of social norms. Bobby’s life is rife with examples of this, even from an early age.

The problem with Bobby was a social one: from an early age he followed his own rhythms, which where often antithetical to how other children developed. An intense stubbornness seemed to be his distinguishing feature. He was capable of ranting if he didn’t get his way–about foods he did or didn’t like, or when to go to bed (he liked to stay up late), or when to go out or stay home. At first Regina could handle him, but by the time Bobby reached six, he was dictating policy about his own regimen. Bobby wanted to do what he wanted to do–and chose when, where, and how to do it. (Brady 13)

At one point, Brady suggests that the young Fischer would be considered “hyperactive” by today’s standards. This diagnosis is doubtful from the get-go: hyperactivity is an attention deficit, and hyperactive kids struggle with chess. A competent psychiatrist in this day would likely diagnose Bobby with the same ailment that has–rightly or wrongly–been attributed to Einstein: Asperger’s syndrome.

Wikipedia sums up Asperger’s as follows:

Asperger syndrome, also known as Asperger disorder or simply Asperger’s, is an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) that is characterized by significant difficulties in social interaction and nonverbal communication, alongside restricted and repetitive patterns of behavior and interests. It differs from other autism spectrum disorders by its relative preservation of linguistic and cognitive development. Although not required for diagnosis, physical clumsiness and atypical (peculiar, odd) use of language are frequently reported.

Wikipedia goes on to list “restrictive and repetitive interests and behavior” and hypersensitivity in audio and visual perception, both of which were manifest in Fischer. He would often complain in tournaments about harsh lighting and people being too loud. The 1972 World Championship was almost forfeited on account of the sounds coming from television cameras recording the event.

The DSM IV description of Asperger’s can be found here.

Asperger’s can be extremely disabling. Imagine being socially “blind.” One would have difficulty knowing friend from foe, but an equally great difficulty would be in navigating the social web and finding friends in the first place. When two people meet each other, a “dance” goes on to assess whether a friendship will develop. Asperger’s is the equivalent of being deaf to the music.

It is in this context that we can make sense of Fischer’s chess obsession. Young Bobby’s beautiful mind was trying to find a way around a disability. Of various ad hoc remedies that his mother offered (at one point, unable to afford a piano, his mother found someone to teach him the accordion), chess came out as the forerunner, a game that requires impeccable perception, analysis and timing. As a corollary, expertise at the game would give Bobby entry into a much needed social circle.

If it is the case that Bobby had Asperger’s, it would have been impossible for Regina to find such a diagnosis for Bobby. While Hans Asperger first described the disability in 1944, it was not popularized or accepted in the medical community until the 1980s.

Children and Grown Children Can Be Cruel

In the context of young Bobby’s disability, we can understand much of what unfolds in the rest of his life. In many ways, after deciding to pursue chess, Bobby’s life became simple. On some level, he knew that he would never be accepted as “normal,” but, by becoming the best chess player, he could become king of a world of his own. Those who showed ridicule and intolerance, he would cut from his life, and feel justified doing so, knowing that if nothing else he was better than them on the chess board. But, the only way for the solution to work on the whole would be to become the greatest chess player in the world. Whether he was accepted or rejected, the solution was always the same: to become better at chess. Chess itself has to be a special game to even fill this need, and only a chess player can know how special the game can be. The better the chess player one is, the more one can appreciate it.

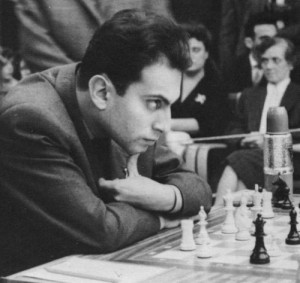

Return now to the World Championship Candidates tournament, in which the 15-year-old Bobby eventually lost to Tal. At that time, the other chess players ridiculed Bobby, and there was a conscious effort to exclude him from the chess elite, where he had already rightfully won his place. The other “candidates” were in their twenties and older. Great chess players, like mathematicians, usually reach their prime in their twenties.

In many ways, the 15-year-old Bobby was just a fish for the twenty-somethings and older grandmasters, far away from his Brooklyn home and supporters, at the Candidates tournament in Yugoslavia. Pictures of him at the tournament show him wearing a ski sweater and corduroy pants, surely unable to afford better, while all of the other players donned tailored suits.

At these tournaments, the masters that are playing are designated a “second” — usually also a master — to assist them in numerous ways, but especially in pre-game and post-game analysis. Russian players would often have a full entourage. At the tournament, even Bobby’s second, Bent Larson, turned against him. Brady’s description of the events is worth quoting at length.

Bobby’s second, the great Danish player Bent Larsen, who was there to help him as trainer and mentor, instead criticized his charge, perhaps smarting from the rout he’d suffered at Fischer’s hands in [the first round at] Portoroz. Not one to keep his thoughts to himself, Larsen told Bobby, ‘Most people think you are unpleasant to play against.’ He then added, ‘You walk funny.’ … Declining to leave any slur unvoiced, he concluded ‘And you are ugly.’ Bobby insisted that Larsen wasn’t joking and that the insults ‘hurt.’ His self-esteem and confidence seemed to slip a notch. (Brady 111)

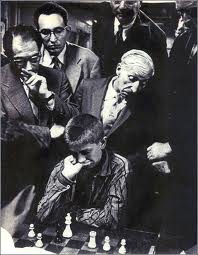

There was also collusion afoot by the Soviet players, with Tal and Petrosian deliberately drawing all of their games and thereby conserving their energy. This is a known fact, but Bobby also worried that the Soviet players were guilty of a more pronounced form of collusion, discussing games while in progress, thereby combining forces against him. Whether or not they were doing so, Tal played to this fear, getting up at crucial moments of the game speak in Russian with the other Soviet players. He also used other psychological tactics against Bobby.

Tal, in a seeming bid to increase Bobby’s irritation, also offered a slight smile of incredulity after each of the American’s moves. … Fischer, deciding to use Tal’s tactics against him, tried producing his own stare, and even flashed an abbreviated, sneering smile of contempt. But after a few seconds, he’d break eye contact and concentrate on … the action on the board.

Tal was an encyclopedia of kinetic movement. All in a matter of seconds, he’d move a chess piece, record the action on his score sheet, position his head within inches of the clock to check the time, grimace, smile, raise his eyebrows, and ‘make funny faces,’ as Bobby characterized it. …

The Russian would look at Bobby from near or afar, and begin laughing, and once in the communal dining room he pointed to Bobby and said out loud ‘Fischer: cuckoo!’ Bobby almost burst into tears, and for the first and perhaps only time during the tournament, Larsen tried to console him. ‘Don’t let him bother you.’ He told Bobby he’d have an opportunity to seek revenge … on the board. (Brady 113)

Fischer would not have his revenge, losing all four games against Tal in the tournament. It is worth noting that Bobby did not take the opportunity to make fun of Tal’s deformed right hand. Tal went on to win the World Championship in 1960, and his psychological dominance of Bobby surely helped him to get there.

In a tournament years later, Bobby would get his revenge on Tal. Tal, up to his old tricks, wasted ten minutes staring Bobby down before making his first move, perhaps looking for weakness. Bobby, now prepared, disregarded it and beat him.

The Unspeakable Article, Again

With these factors in mind, we can once again return to Ginzburg’s article. I think that it is not too far-fetched to point to Ginzburg’s article as the original source of Bobby’s irrational anti-Semitism. What Ginzburg did that was so devastating was similar to what Tal did: it exposed Bobby’s weaknesses to plain view in an unsympathetic way. Perhaps the lowest blow was when Ginzberg implied that Bobby disliked his mother. The following is from the Ginzberg article.

Bobby: ‘She and I just don’t see eye to eye together. She’s a square. She keeps telling me that I’m too interested in chess, that I should get friends outside of chess, you can’t make a living from chess, that I should finish high school and all that nonsense. She keeps in my hair and I don’t like people in my hair, you know, so I had to get rid of her.’

Ginzberg: ‘You mean that she moved out of the Brooklyn apartment you lived in?’

Bobby: ‘Yeh, she moved in with her girl friend in the Bronx and I kept the apartment. But right now she’s away on this trip with those people [the pacifists] for about eight months. I don’t have anything to do with her.’

That Ginzburg betrayed the young Bobby is beyond debate. Even if he did not embellish, he posed as a friend from the Bronx and took the most seedy elements of a five-hour conversation and used them to his benefit, and against Bobby’s. This of course does not justify the Bobby’s anti-Semitism, but my contention here is that this may have been where Bobby’s anti-Semitism was born. The reasoning goes as follows. On account of his disability, Bobby was unable to tell friend from foe. Instead of going on a case-by-case basis, in a misguided attempt at self-preservation, Bobby would generalize when injured badly. Tal had injured Bobby; Tal was Russian; therefore Russians are out to get Bobby. Ginzburg had injured Bobby; Ginzburg was a Jew; therefore Jews are out to get Bobby. Although he would likely never admit it, Bobby was essentially afraid. The argument is that the flawed logic was precipitated by the disability.

We can use this model of “generalizing” to also understand Fischer’s fear of the press (also originating with Ginzburg) and the U.S. government (originating in the F.B.I.’s hounding of his “communist” mother and further strengthened upon their persecution of him for his rematch with Spassky). The same flawed reasoning would play itself out again and again in Fischer’s life. One can see Fischer’s fear of the press in an interview he did for the Dick Cavett show.

Whether or not Bobby’s anti-Semitism originated in the way described, it was of course an abomination. Many of Fischer’s closest friends and mentors were Jews, and Bobby himself was likely a full blooded, if not practicing, Jew.

After the tournament in Yugoslavia, Fischer later became friends with Grandmaster Lilienthal, mentioned at the start of this article. Brady relates the following.

When Bobby aired his views regarding the Jews, Lilienthal stopped him: ‘Bobby,’ he said, ‘did you know that I, in fact, am a Jew?’ Bobby smiled and replied, ‘You are a good man, a good person, so you are not a Jew.’

Conclusion

It was readily apparent to anyone who knew the young Bobby that he was a special case, and needed to be protected. To a great extent, he was protected by the chess community. Selfless protectors and benefactors came from all around: Carmine Nigro, who tutored and befriended the young Bobby; Jack Collins, who took Nigro’s place when Nigro moved away and fed him dinner almost daily; Borris Spassky, who displayed a fierce loyalty to Fischer throughout his life, and viewed him like a “brother.” Perhaps most impressive, the entire Parliament of Iceland came to his defense when Fischer was imprisoned in Japan on account of the George W. Bush administration revoking his passport, attempting to take him to task for playing the cash game against Spassky in Yugoslavia, years prior, in violation of a trade embargo. Bush’s targeting Bobby in the “war on terror” was as irrational as the F.B.I.’s targeting of Regina during the time of McCarthyism. The Icelandic government offered Bobby full citizenship, in defiance of the U.S. government. In a display of civility and humanitarianism, a committee was formed to care for Fischer in Iceland, where Fischer spent the final years of his life.

In all, the story of Fischer’s life is one of unsung heroes and ignorant villains. It is unfortunate that the U.S. government and the press at the time would have to be grouped with the latter. The press, perhaps, can be forgiven, because, as always, they were just trying to get a story, and it was not an organized, deliberate effort. But the U.S. government’s treatment of the misunderstood genius should not be forgiven or forgotten any time soon.